Bird Strikes (Feathered and Featherless)!

Bird Strike! No not industrial action, but a collision between an aircraft and our feathered friends (or actually our featherless friends otherwise known as drones).

What should you do?

Having a bird strike in an aircraft can vary from a non-event to a full-blown emergency, so here’s a bit of insight into best practice if you find yourself in this situation.

Our feathered friends share the air with us. In fact, they were there first, so it’s us that are the intruders into their domain. As such, instinct is in-bred into our fellow aviators and there are a few rules that they follow that are worth bearing in mind when considering the likely action a bird will take in a given situation.

Birds are generally nervous and tend to evade threats and danger rather than confronting it (with the exception of a particularly stupid breed called a pheasant – more on this later).

Whilst on the ground they constantly look for danger (usually from above), and you will find they generally sit on the ground facing the wind ready for "immediate" departure should the need arise. Similarly, like us, birds always land into wind.

You should always remember that airborne birds always make use of gravity to assist their powered flight to evade mid-air collisions. In other words, birds always “dive” out of the way.

So armed with these little pieces of information, let’s consider some scenarios where we have a “shared airspace” situation.

Departure Phase

Whilst taxiing to the runway, look at the surrounding area and make a note of where any large gatherings of birds are. If on the ground, consider requesting a “bird scare run” by the ground crew (give them a heads up) so that they can perform this task just before your departure.

Remember that birds will take off into wind, so pay particular attention where there is a cross-wind present during your departure that would involve the birds flying across the runway in front of you as you are taking off.

Make use of the landing/taxi/strobe lights on the aircraft to become even more visible to our smaller aviators. Some operators have a policy to have the landing light on for the whole flight – both for conspicuity to other aircraft, and also for bird avoidance.

Where birds are present during departure, you might consider performing a "best angle" (Vx) climb profile to ensure you gain altitude more steeply to give birds more time and room to "dive" under your aircraft if a conflict exists (remember you should always aim to climb because the bird will always dive).

If a bird strike occurs, this may or may not be obvious depending on the size of the bird, and the part of the aircraft involved in the strike. Even small birds can result in significant damage, so bird strikes should not be taken lightly.

If room allows, reject the take-off (now you know why you get taught these) and bring the aircraft to a safe stop. Better to be on the ground with a potential problem than in the air with one. Don't forget, there are many scenarios that need considering; here's a few (you can think of others) but all become much more manageable if we are not in the air!

- Bird strike blocks the pitot head resulting in an erroneous airspeed indication

- Bird strike blocks the static vent resulting in an erroneous airspeed AND altitude indication

- Bird strike damages a radio aerial resulting in loss of communications

- Bird strike obliterates forward visibility through the wind-shield

- Bird strike causes wind shield to shatter with bird remains entering the cockpit (believe me when I tell you the smell is sickeningly awful too). This can also lead to personal injury or incapacitation of the pilot. The hole in the wind shield can also significantly increase drag.

- Bird strike causes damage to undercarriage (see later specifically for retractable undercarriage aircraft)

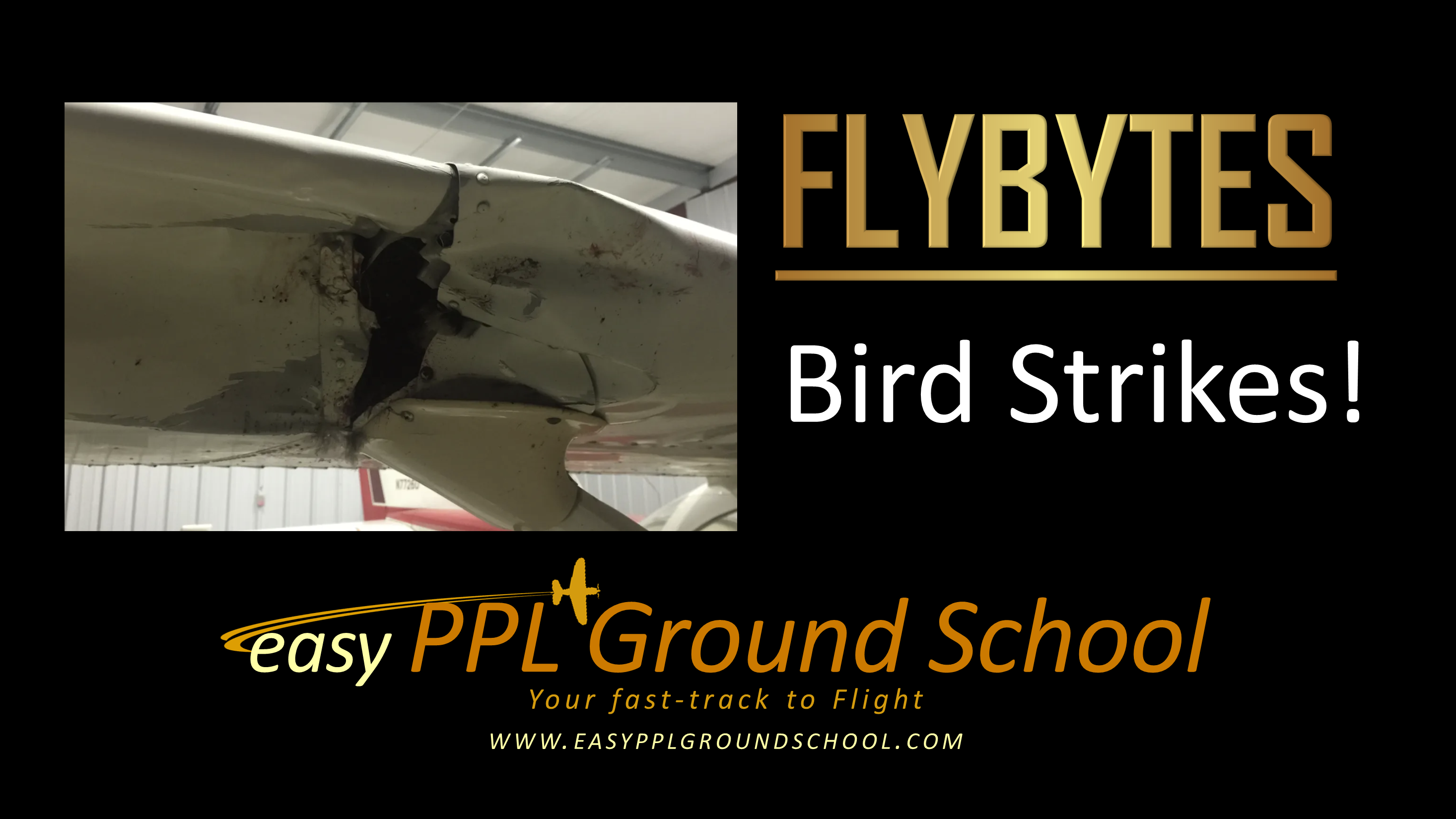

- Bird strikes can lead to aerodynamic performance reduction; large dents or gaping holes in leading edges reducing lift and increasing drag

- Bird strikes can cause damage to flaps or operating mechanisms that might cause an asymmetric flap situation when flaps are operated

Assuming the aircraft reaches airborne status either before the bird strike, or where the pilot elects to continue the take-off, then we need to think about some additional considerations.

Do not change the configuration of the aircraft. Do not raise take-off flaps (risk of asymmetric flap). Specifically for aircraft with retractable undercarriage, do not retract the undercarriage! If the bird strike has bent an undercarriage door, there is a risk that the gear may get jammed in the up position, or worse, you may end up with asymmetric gear (one up, one down).

In all cases, you will not be able to see the extent of the damage from the cockpit, so it's probably best to not continue with your planned flight. Instead, opt to perform a circuit, followed by a normal landing after a fly-by for a general/undercarriage inspection.

During the cruise

Although quite rare, this is an occurrence that could manifest itself. Bird strikes at cruise speed will result in more damage to the aircraft. When confronted with a bird (or worse still a flock of them), it is always best to attempt to climb over them, since birds will dive out of the way by instinct.

Once again it is important not to change the configuration of the aircraft without careful thought and forward planning. For example, reduce speed to flap limiting and approach speed at altitude to check the slow speed handling characteristics of the aircraft. Deploy flaps at altitude again to check operation, leaving room (altitude) and time (via altitude) to sort any problem out if an issue occurs. The same applies to lowering undercarriage – perform this at altitude and in good time to assess the process, but once down, leave it down!

During landing

Fly the aircraft! Try not to become distracted (much easier said than done).

There are no hard and fast rules here as to whether to continue with the landing or go-around for an inspection before attempting a further landing. It’s all very situation specific that needs some thought. Here’s a couple of examples:

- Bird strike breaks the wind shield and enters the cockpit. The incident will be a shocking experience, so the pilot is probably not in a great state of mind to pull off a safe landing immediately, hance a go-around might be the best option. However, the increase in power is likely to cause an additional wind-blast into the cockpit which will also exacerbate the situation.

- Bird strike causes undercarriage damage. Whilst it makes no difference to the outcome of a landing whether before or after a go-around is performed, consideration should be made into the preparedness of everyone for the outcome. By performing a go-around and making the radio call, gives ground crew time to be in a better position with fire crews deployed for a landing involving damaged undercarriage.

And afterwards

Once the feathers have settled, bird strikes are an occurrence that must be reported (by law) to the authorities by the pilot. A formal Mandatory Occurrence Report must be made.

Oh, and that stupid bird

Pheasants are stupid. Period. Pheasants are the only bird I’ve come across that will attack the rotating propeller of an aircraft whilst it is on the ground. Inevitably, the aircraft always wins that battle, but the message from Darwin to the future pheasant gene pool has not yet got through.

Back to Flybyte Articles